Written by Mystic Ode with Special Thanks to Glitterberri

[Last Updated: 3/2/2026, wording adjustments]

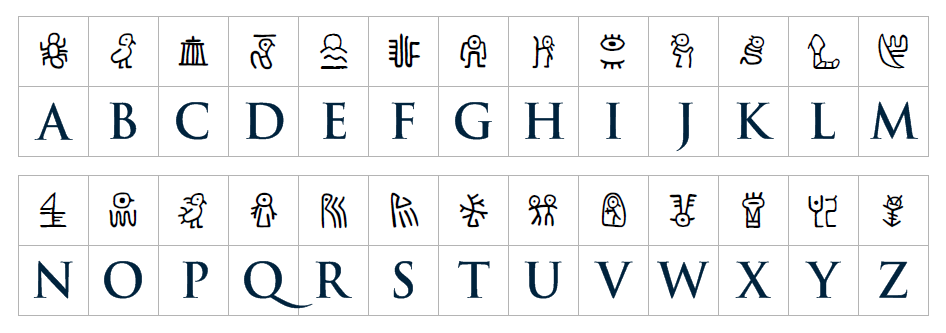

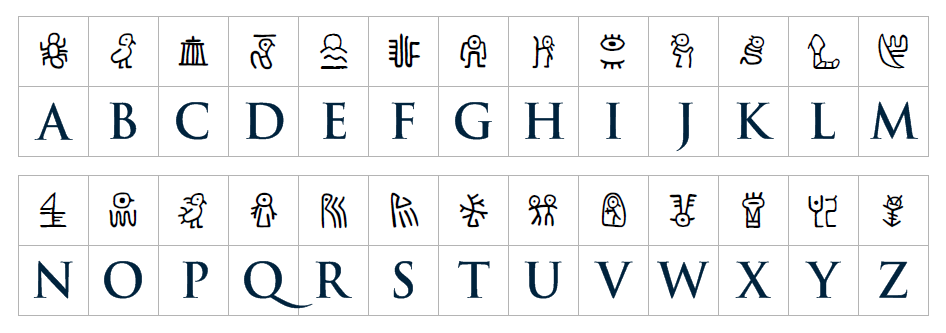

This webpage serves as an attempt to uncover the process used to create all the lines in e-koʊ (both used and cut) that utilize the hieroglyphic script seen above. Nearly all of its contents are speculative observation. You are free to challenge almost anything I suggest about this language if you find the evidence to counter it, because we will likely never recieve confirmation of any kind and these are only my best guesses, based on what little material we have to work with.

The fandom community surrounding Fumito Ueda’s work commonly refers to this language as ‘The Runic Language’ (or ‘Runic’ to be concise). However, this is not an official term as far as I can tell, and the developers have usually referred to it as "yorudas Language”.

At time of writing (1/21/26), this is what is listed on the Team e-koʊ Wiki (which denotes our community’s collective understanding) regarding the process of decoding this language:

Translating the language manually

|

To clarify for those unaware: yorudas language is based in Japanese, and 'Romaji' is used to describe Japanese terms being 'romanized' or represented by letters of the English Alphabet. Reversing the Romaji transcription of the original Japanese script and erasing letters was how Team e-koʊ created these captions... in the broad strokes, but there's a lot this description is leaving out.

Even so, this passage has been almost entirely untouched since the Runic Language page’s creation in 2009. The community has been satisfied by it for all this time. But through my findings, I hope to change that. I hope this article sparks some motivation in others to further explain the linguistic details of ICO's world and complete the gaps I can't fill alone. But, failing that, it should still provide you with some neat trivia.

You will see my observations and notes first, before you see the script lines I picked apart.

I’ve organized things this way to help orient readers, and show the patterns you can latch onto as you read.

Number references (e.g. See: 00)

apply to the

script

section’s File Numbers, which

categorize each line.

The way this has been described by other sources is incredibly lacking. Many end up with a misconception that reversal is uniformly applied to an entire sentence. This is rare to occur, usually only happening when the sentence is actually one word. Reversals also don't reverse one word at a time. They don't even always adhere to the bounds of individual words. Instead, letters are reversed in groups. While they often start and end with completed terms, some groups seem to be capable of breaking words in half, and they all wildly vary in size.

[As an exam][ple of this] [reversal system]: maxe na sasiht fo elp metsys lasrever

(Note: The groups themselves do not change order, they remain static while their contents are reversed.)

Though letter erasure can sometimes follow a 'Remain-Erase-Remain-Erase' pattern that conveniently targets the vowels of many Japanese words, there is no consistent pattern to which letters get removed. So vowels are not exclusively the target. However, the amount of letters left remaining does have some consistency, depending on how many words are produced per reversal group.

There are reversal groups that produce one word, two words, and three words. 'Word' is very loose in this context, of course. Basically, it's anything in Yorda's Language that isn't separated by a space. [anata wa] becomes [ath n], so that's what I'd call a two-word reversal group. [iidasu no da] becomes [anuy] so that's a one-word group.

And it is actually pretty hard to tell, with some of the more packed captions, where there are spaces between hieroglyphs, so I might even be wrong about some of this. But these are the patterns I noticed:

Among one-word reversal groups, there is only one instance of a word ending up with 5 letters: [modoranai] becomes [yurom]. All other one-word groups I've found, no matter how many letters they contain in Romaji, always end up with 2-4 letters in their YL (Yorda's Language) word. This means if you see a 1 letter word in YL, it likely came from a two or three-word reversal group.

Among one-word reversal groups, it's very very common to see groups with 6 letters in Romaji get reduced to exactly 3 in YL:

haitte [eti]

yoruda [yld]

kaette [etk]

kaasan [nsk]

omae wa [awm]

nani wo [owi]

koko wo [ock]

kaerou [orq]

inaiyo [yni]

hito wo [wti]

The only found exceptions seem to be 'yamete' (etam, 4 letters) and 'kita no' (on, 2 letters).

All one-word groups containing 3-5 Romaji letters become a 2 or 3 letter word in YL. All one-word groups with 8-11 letters in Romaji become a 4 letter word in YL, with the aforementioned exception of 'modoranai', which became a 5 letter word.

Two-word groups are never smaller than 7 Romaji letters. And are always split such that they never produce a word with more than 5 letters. But as I said before, 1 letter words can (rarely) be produced by these (and three-word) groups.

Where the split occurs changes depending on the word.

Some are based in verb conjugation: [想って/いる のに] or [omotte/iru noni].

Some are based in where kanji end and hiragana begins: [気持/ち も] or [kimo/chi mo]

Some are placed between kanji that can be read as individual terms: [邪魔/者] or [jama/mono]

Some might be placed where one word can become another word (if that makes sense?): [zuib/unto] is a split that can't even be transcribed in Japanese because 'bu' is one mora (ぶ). But though 'zuib' doesn't make sense, 'unto' is its own adverb.

Some might be placed at the end of a prefix(? if that's a valid term): [何れに/せよ] or [izureni/seyo] as opposed to another, similar term: izurenishitemo. In short, terms that are etymologically linked, but feature a different end, may be split at the point of variation. This may also explain why [watashi] is always split between the wata- and -shi, due to the existence of the adjacent pronoun: [watakushi].

Many splits are exactly where you expect a space to be: between a set of Romaji words.

But others still I do not understand well, such as [okoras/e] becoming [e srq]. That example in particular makes me wonder if I've interpreted the text incorrectly...

The information above also applies to how reversal groups can sometimes split words in half...

Anyway, it's harder to gather specific data on the total number of Romaji letters accounted, per word, for two and three-word reversal groups, given I have to be sure exactly where every split is, and be sure that every Japanese word within a group was actually included in the draft where Yorda's Language was made. (I believe some words were likely inserted later. Making the process of understanding how many letters of a total were left behind difficult.)

The maximum number of letters in both the two-word and three-word groups was 19. So it seems there was no specific cap on what would become two-word or three-word groups, you just made three-word groups when you knew you couldn't afford to leave any less than 8 to 10 letters, for the sake of keeping the phrase somewhat discernable.

(with the noted exception of yorudas name)

The following are terms with fairly consistent transformation, and spelling, within the language.

naze = ezn (See: 32, 48, 59) [100% consistent]

saa = ahs (See: 31, 45) [100% consistent] (middle ‘a’ consistently transforms to ‘h’ via a → h substitution)

inai = yni (See: 59, 81) [100% consistent] (final ‘i’ seems to transform into ‘y’ via i → y substitution)

oide = dio (See: 31, 45) [100% consistent]

kaasan = nsk (See: 46, 61) [100% consistent]

waka(-ranu or -ranai) = arkw

wakatteru wa = wur tkw

wakatte = e akw (See: 48, 53, 58, 67) [100% consistent]

The ‘kw’ of ‘waka’ is consistently left alone. While different forms of the verb change the first half of the term.

daijoubu desuka = ad boju (See: 77, 81) [100% consistent] (however the addition of 'desuka' is a guess based on observed patterns, and not a confirmed fact)

hontouni moushiwakenai = ynst (See: 50, 79) [100% consistent] (however the Japanese term I equated it with is a guess based on observed patterns, and not a confirmed fact)

omae wa = awm

omae wo = owm

omae ga = agm (See: 54, 55, 57, 66, 69)

[83% consistent] (See Outlier: 49 (This is a unique instance of w → h substitution for this term)).

The ‘m’ of ‘omae’ is consistently left alone and then paired with an untouched follow up particle (be it wa, wo, or ga).

We see a similar case with ‘anata’ and ‘watashi’. Making it a potential rule of all pronouns to have their particles incorporated in full.

anata wa = aht n (See: 9, 46, 61) [100% consistent] (‘wa’ consistently transforms to ‘ha’ via w → h substitution)

One instance of ‘anata’ was spelled ‘htna’ (See: 21), potentially making it less consistent.

However, it’s unclear if the original draft really included the ‘wa (は)’ particle or not. The term could be paired with the start of ‘hitori’ to explain the ‘h’.

watashi wa = aws atw

watashi wo = ows atw

watashi no = onhs atw

or just ‘atw’ when without particle (See: 53, 56, 59, 60, 62, 63, 68, 79) [80% consistent] (See Outliers: 20, 50)

Terms in Japanese that mean “yes”, tend to become the actual English word, reversed in yorudas Language: sey.

These terms include ‘ee’ (ええ) (See: 68) and ‘un’ (うん)

(See: 83).

When writing in yorudas Language, one can substitute certain letters for others. This allows the limited Romanization of Japanese to include all 26 English letters, while also diluting the meaning of words.

A → H (See: 31, 45)

CH → T (See: 52, 53, 61)

E → A (See: 72, 76)

H → N (See: 56) or W (See: 49)

I → Y (See: 49, 50-50, 52, 56, 59, 60, 64, 65, 67, 70, 74, 79-79, 81) or U?(See: 62, 77, 81)

K → Q (See: 29, 47, 49, 52, 53, 57-57, 62, 67, 68, 74) or C (See: 20, 50, 56, 57, 62, 69) or X (See: 54, 86)

N → M (See: 46) or U (See: 60, 68)

O → U (See: 69, 72)

R → L (See: 57, 64, 68 [Excluding instances of yorudas name]) or S (See: 9)

SH → X (See: 50)

W → H (See: 9, 46, 49, 61)

? → P (See: 47)

? → V (See: 47)

CH → T

‘CH’ is the

softer alternative to the dental ‘T’ sound. And Japanese

speakers, over the course of centuries, dropped the more precise ‘ti’

in favor of the softer ‘chi’. If you look at any hiragana/katakana chart

for the language, you will notice other consonants are often paired

cleanly with their vowels (na, ni, nu, ne, no) but T is not one of

those cases (ta, chi, tsu, te, to).

‘Team’ (チーム)

is a good example of a loan word’s ‘ti’ (or ‘tee’) sound

becoming ‘chi’.

H ↔ W

The particle は (ha) has a special use case in Japanese. When used to indicate the topic of a sentence, it is instead pronounced ‘wa’ without changing the character used (typically, ‘wa’ is associated with this character: わ). This may be why the letters are allowed to swap places in File 49.

I → Y

In English loan words that end with ‘Y’ (often creating the ‘ee’ sound) Japanese speakers use morae that end in ‘I’, which for them, is pronounced just the same (‘ee’). ‘Lucky’ (ラッキー) and ‘Canopy’ (キャノピー) are exmaples of this.

K → X

To pronounce English loan words such as ‘Expo’ (エキスポ) or ‘Box’ (ボックス), Japanese speakers will use the ‘ki’ or ‘ku’ mora (with the i or u’s pronunciation devoiced), in tandem with ‘su’, to sound out the ‘X’ (ksu). Thus creating an association with the letter K.

K → Q

‘K’ morae are used for English loan words featuring Q, such as ‘Quest’ (クエスト) or ‘Quark’ (クォーク).

K → C

As with the entry above, ‘K’ morae are used for many English loan words featuring C, such as ‘Capsule’ (カプセル) and ‘Cake’ (ケーキ).

R → L

“Japanese only has

a singular liquid phoneme /r/ which is usually pronounced as an

alveolar tap [ɾ], but can also be pronounced as an alveolar lateral

approximant [l]. This is in contrast to English, which has two liquid

phonemes, /r/ and /l/, usually pronounced as the postalveolar

approximant [ɹ̠] and the alveolar lateral approximant [l]

respectively. As a result, when translating names into English,

especially fictional names that are intended to sound foreign, either

R or L can be used.” |

SH → X

This is more of a Chinese association, but due to the undeniable influence of the Chinese language on the Japanese language, it should count among the Japanese associations, I think. X, as written in Chinese, is pronounced with a sound comparable to the ‘SH’ sound in English.

e → a / n → u

These letters are diagonal reflections of each other in their lowercase forms.

H → N (h → n) / N → M (n → m)

These letters bear similarities in their structure, for both upper and lowercase.

A → H

These letters bear similarities in their structure, in uppercase form.

O → U

An O could be perceived as a ‘closed’ U? Uncertain.

r → s

Due to their hook-like quality, perhaps these letters were considered structurally similar in their lowercase form? Uncertain.

Yet Unclear Reasonings: I → U

This is not a rule of the language, so much as it is a consequence of development that becomes an obstacle to us, as decoders.

A few of The Queen and yorudas lines, constructed at an unknown point in time, were revised in structure and vocabulary for the game’s New Game+ captions (first included in the Japanese release, on December 6th, 2001). Because we rely so heavily on the NG+ translation feature to guide our understanding of yorudas Language, these revisions inadvertently muddle the original meaning of the hieroglyphic captions.

Luckily, the revisions are not often drastic.

Most involve only a few words being changed, seemingly into synonymous terms that either carried slightly different implications or sounded better to the developers. Even so, it puts us in the difficult position of having to guess whether a series or strewn letters was encoded by some unknown rule, or if what we see are actually the remnants of an earlier draft. Some remain unclear even now.

“The reason why we use a

constructed language is that we want to make the world as an

unknown one, not as in a certain place or age in the real world.

Besides, if we use natural languages like Japanese or English in

the game, players can understand what the characters are saying,

so we have to decide the lines completely before the voice

recording, including hint voices. Instead if

we use a constructed language, we can change the lines even at the

last part of development, corresponding immediately to the

tuning. After all we are creating a game, we want to adjust it

until the very last.” |

(Note:

I am a novice when it comes to Japanese, so identifying where the

spaces should be placed in the Romaji transcription was difficult at

times.

I’m sure I’ve made mistakes, so please feel free to double

check my work.)

Key:

[] = Reverse selected letters (Read right to left)

Grey Text = Letter Removed

Red Text = Unknown Transformation

Orange Text = Commentary

{ } = Substitution Use

→ = Word Repositioned

Black Highlight = Mystic's Personal Confidence

For those of you curious which lines made it to final release, their borders will be highlighted in Gold.

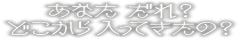

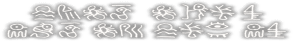

File 9:

anata dare?

doko kara haitte kita no?

Glitterberri suggests an earlier draft used:

あなたは (anata wa)

[anata {w}a

da{r}e]

[doko]

[kara] [haitte]

[kita no]

esad

aht n

okd

ar eti on

File 16:

yoruda...

yo{r}uda

yld

File 20:

watashi wa koko wo

hanarerarenai no...

[watashi

wa] [ko{k}o

wo]

[hanare][rarenai

no]

aw stw ock

erh nia era

File 21:

anata hitori de itte

[anata

hito][ri de] [itte]

htna dir eti

File 29:

ano hito wo

okorasete

shimatta wa...

[ano] [hito wo]

[o{k}orase]

[shimatta

wa]

on wti e

srq atms

File 31:

saa kaette oide yoruda

[s{a}a] [kaette] [oide] yo{r}uda

ahs

etk dio

yld

File 32:

yoruda

naze

damatteiru no da?

yo{r}uda

[naze]

[damatte][iru

no da]

yld

ezn e amd nur

File 45:

saa oide yoruda

[s{a}a] [oide] yo{r}uda

ahs dio yld

File 46:

anata nanka

watashi no kaasan janai wa

Glitterberri suggests an earlier draft used:

あなたは (anata wa)

Mystic suggests an earlier draft used:

本当

(hontou) instead of 'nanka watashi no' and inserted こと

(koto)

[anata

{w}a]

[hontou ??]

[kaasan]

[koto ja][{n}ai

wa]

aht n nu otn

nsk ajk wiam

File 47:

kikiwakenonai ko da...

[{k}ikiwakeno][nai ko da]

onk wkq adpv

File 48:

naze wakaranu

[naze] [wakaranu]

ezn arkw

File 49:

omae wa

soto no sekai deha

ikite wa ikenai

no da yo

[omae

{w}a]

[soto no

sekai]

[de{h}a]

[i{k}ite wa {i}kenai

no da yo]

ahm

iks ont we

ydn

ank ytq

File 50:

kitto

hidoi koto wo iwareta no ne

watashi no sei de gomennasai...

Mystic suggests earlier drafts used:

所為で 私 本当に 申し訳ない (sei de watashi hontouni moushiwakenai) instead of 'watashi no sei de gomennasai'

[{k}itto]

[hidoi koto

wo] [{i}wareta no ne]

[sei de

wata{sh}i

hontouni

moshiwakena{i}]

tic

ow dh rwy

ynst

xtw dies

File 52:

zuibunto machikutabireta yo

[zu{i}bunto]

[ma{ch}i{k}utabireta

yo]

onu byz ytr

batuq itam

File 53:

yoruda

watashi no kimochi mo

wakatte okure

yo{r}uda

[watashi

no] [{k}imo{ch}i

mo]

[wakatte

okure]

yld

onhs atw

mt

mq e akw

File 54:

omae wo kurushimetakunai nda yo

[omae wo] [{k}urushimetaku][nai nda yo]

owm kt msx yda

File 55:

konnani

omae no koto wo

omotteiru noni

[konnani]

[omae no

koto wo]

[omotteiru noni]

ian

nk owm

nnur

etm

File 56:

sonna watashi wo oite

doko he ikou toiu no dai?

sonna [watashi wo] [oite]

[do{k}o

{h}e ikou

toiu no da{i}]

ows

atw eti

yduk

incd

File 57:

omae

wa koko de shika

ikirarenai no dayo

[omae

wa] [{k}o{k}o

de shi{k}a]

[ikira{r}enai no dayo]

awm

aqhs

edcq nlrk

File 58:

wakatteru wa...

[wakatteru wa]

wur tkw

File 59:

deha naze watashi no soba ni inai

[deha] [naze] [watashi no] [soba ni ina{i}]

ahd

ezn onhs

atw yni abs

File 60:

watashi wa modoranai

[watashi wa] [modora{n}a{i}]

aws atw yurom

File 61:

kaasan

anata wa machigatteru wa

[kaasan]

[anata

{w}a]

[ma{ch}igatteru

wa]

nsk

aht

n rt agtm

File 62:

watashi wa jibun no

ikitai you ni ikiru

[watashi

wa] [j{i?}bun no]

[i{k}itai

you ni]

[i{k}iru]

aws atw

obuj nytq rc

File 63:

sono daishou toshite watashi no

inochi ga ushinaware you tomo

sono

daishou toshite [watashi

no]

inochi [ga] ushinaware you tomo

utt onhs atw

ag ar omdnh

File 64:

tsuminonai shuzoku no gisei noueni

ikinagaraeru yori zutto mashi dawa

[tsumino][nai shu?zoku?] [no gisei noueni]

[ikinaga{r}aeru] [yori] [zutto] [mash{i}] dawa

omu wkz yus

ei sg

rl agn ry

otzym

File 65:

nani wo iidasu no da? yoruda

[nani wo] [i{i}dasu no da] yo{r}uda

owi anuy yld

File 66:

arehodo sunao datta omae ga...

Glitterberri

suggests an earlier draft used:

そんなに (sonnani) instead of 'arehodo'

[sonnani] [sunao datta] [omae ga]

i an td nus agm

File 67:

koredake itte mo

wakaranai no kai?

[koredake] [itte mo]

[wakaranai

no {k}a{i}]

ekd er omt

yq nia arkw

File 68:

ee

watashi no kimochi wa kawaranai...

[yes]

[watashi no]

[kimochi

wa] [{k}awa{r}a{n}ai]

sey

onhs

atw

awmi ulwq

File 69:

omae wo sokomade kaetano wa

sono tsuno no haeta kodomo kai?

Mystic suggests an earlier draft used:

いけにえ (ikenie) rather than ‘tsuno no haeta’

[omae

wo] [sokomade]

[{k}aetano

wa]

[sono]

[ikenie]

[k{o}domo kai]

owm

edm ok wntc

nos enk omduk

File 70:

kono ko wa kankeinai wa!

[kono ko wa] [kankeina{i} wa]

aw knk aw ynknk

File 71:

izureniseyo sono ko niwa

sukoshi oshioki wo shinai to ne

[izureniseyo]

fff

Supposedly laughter. ‘fu

fu

fu

’. Unsubtitled in the Japanese captions. Likely included here as the only opportunity to show what the hieroglyph for 'f' looked like.

oye neruz

File 72:

[continuing from above]*

[s{o}no ko

niwa]

sukoshi

[oshioki

wo shinai

to n{e}]

awnk onus

ant ani ikis

* File

72’s first playthrough captions are a continuation of the sentence

that began in File 71.

However, the ‘File 72’ found amid the

New Game Plus captions provides a new sentence that wasn’t actually

processed into yorudas Language:

File 74:

saa jamamono wa inaku natta

issho ni kaerou yoruda

Mystic suggests an earlier draft used:

去れ (sare) instead of 'saa'

[sa{r}e] →yo{r}uda

[jamamono]

[wa inaku natta]

[issho n{i}]

[{k}aerou]

las yld

n amj tuk ys orq

File 76:

yamete!

[yam{e}te]

etam

File 77:

daijoubu?

Mystic suggests an earlier draft

used:

大丈夫 ですか (daijoubu desuka) instead of just 'daijoubu'

[da{i?}joubu desuka]

ad boju

File 79:

gomennasai

watashi no sei de konna kotoni

Mystic suggests an earlier draft

used:

本当に 申し訳ない 私 本当に 申し訳ない (hontouni moushiwakenai watashi hontouni moushiwakenai) instead of 'gomennasai watashi no sei de'

[hontouni moshiwakena{i}]

[watashi

hontouni

moshiwakena{i}] [de?] [konna

kotoni]

ynst ynst

atw ed intk ur

File 81:

inaiyo kiechatta…

mou daijoubu yo

Mystic suggests an earlier draft

used:

大丈夫 ですか (daijoubu desuka) instead of 'daijoubu yo'

[ina{i}yo]

[kiechatta]

[mou]

[da{i?}joubu desuka]

yni at ek

um ad boju

File 83:

un...

[yes]

sey

File 86:

Ato mousukoshi yo

[Ato mou][su{k}oshi yo]

um oty sx

File 91:

arigatou…

nonomori

nnmr

File 112:

sayonara

[sayonara]

arn oys

The means of both constructing and reverse engineering yorudas language are far more complex than many have been led to believe.

It was said in the ‘Walking with Giants’ interview (found among the bonus features of the e-koʊ & Shadow of the Colossus Collection), that those on e-koʊs planning team used to call the process of converting the script to yorudas language: Self Conversion (自分変換).

This moniker is faintly elaborated on by Kenji Kaido with the following translated quote:

“Each person has developed his own individual conversion rule based on their feel and experience.”

The planners included Junichi Hosono, Kei Kuwabara (responsible for the majority of the language’s hieroglyphic visuals), Tsutomu Kouno, and, of course, the duo of Kenji Kaido and Fumito Ueda. So this quote implies a minimum of five overlapping rules, one created by each individual.

However, it is difficult to accredit individual rules, and whether these rules were applied evenly across all the dialogue.

For instance, would the many details of the letter substitution system count as one rule, or several? And why are substitutions absent for some lines, but not others? Was the absence a part of an existing rule/pattern, or was it simply because a planner was not present to use their conversion method at the time of the script addition/adjustment?

In truth, there may be no rhyme or reason to some of these decisions, beyond what appealed to the developers at the time.

But even so, a better understanding of these conversions is possible. I think my effort has made that much clear.

Please contact me via the options listed on the Index page if you believe you've noticed something important to add to this article. Alternatively, you could also use this site's guestbook, to make it a more open discussion.